Earlier this week I went to a panel discussion burdened with the question, Is Crime the new Literary Fiction? The panel comprised Lee Childs, Sophie Hannah, John Banville (as his crime writing alter ego Benjamin Black) and Peter James. The chairman was not Mark Lawson as advertised, but someone else, who assumed we must know who he is; unfortunately I don’t.

I wanted to go to hear the discussion because I like reading crime fiction, and also because I enjoy hearing crime fiction writers getting bent out of shape and aggravated about the arbitrary distinctions drawn in the world of fiction between literary and genre. I should confess straight away, however, that I have never read any books by any of the writers on the stage, even though I would describe myself as a major consumer of the genre. Having listened to the discussion, it’s fair to say that none of them persuaded me that I should be reading their work.

I find it an interesting conclusion to have reached, as usually listening to writers makes me want to read their work, but it has been useful and has crystallised some of my understanding of what I enjoy in the crime genre.

The quality question was dealt with fairly quickly, with consensus that not all crime fiction is first rate, and that some ‘literary’ output is fine, and that perhaps it is most useful to think of genre as an aid to identify the tribe of people who like particular types of books (cue a bitchy remark by Lee Childs about ‘the 64 year old English man who thinks the most interesting people he’s ever met were with him at prep school’ genre created by Julian Barnes.)

In a crime series, the writers suggested that it is the main character which is important; they expect their readers to remember the characterisation of the hero detective, while few will recall the plot once the book is finished. The plot is needed, but only as the engine to illuminate character. With this I am in total agreement, where I differ is on a very strong opinion expressed by Lee Childs that he hates the idea of his protagonist going on any sort of ‘journey’. He is determined that there should be no learning curve or development of the character of his hero, who learns nothing, and never changes, as he knows everything he will ever know or need to know, already.

While I too dislike the current obsession with characters’ journeys because it seems to be an unnecessarily rigid orthodoxy, if I think about the crime fiction series that I enjoy, a key element of them is the development of the hero, usually getting older and more world weary and cynical; I’m thinking of Ian Rankin’s Rebus books or James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheau series.

There was a difference of opinion in the discussion about how outlandish or realistic the scenario in crime fiction might be, and if the writers have a political agenda. The only thing that was in common was a dislike of authority figures, although no-one had any particular sympathy for the little guy.

My preferred crime writers tend to deal in contemporary issues and a tangible sense of place and time; Ian Rankin in present day Edinburgh, and James Lee Burke in Louisiana. Where there are chaotic and confusing times, these writers seek to make sense of it by using the conventions and order of the crime genre, while providing something much more than just a puzzle.

It was interesting to hear that none of the writers on the panel have a clear and fixed idea of the outcome of their novels at the time when they first start writing them. This affords them a sense of discovery and enough interest to keep them writing; and writing quickly with a lot of impetus and momentum is key to writing an exciting novel, it seems. There’s a lesson there for us all.

TBM

/ November 15, 2012I’ve only heard Peter James speak. I haven’t read any of his novels, but I was surprised when he claimed that if William Shakespeare wrote today he would write crime fiction. I found that odd since during his day, Shakespeare dabbled in many different fields.

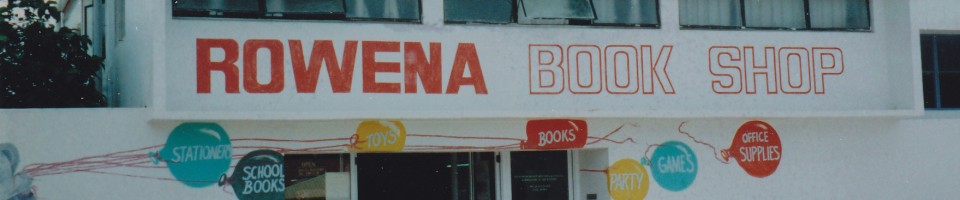

rowena

/ November 15, 2012I don’t think P james suffers from a poor opinion of himself and he did touch on his Shakespeare theory – I think the point is that in Tudor England when few people could read, you maximised your audience by writing plays. In Victorian times Dickens found his audience by writng episodic cliff hanger novels, and so on. So I would say that the theory would lead to a supposition that if they were alive today both Shakespeare and Dickens would be writing soap scripts….